American shad defied predictions of a big spring spawning run this year and veered away from most Bay tributaries. The Chesapeake was not alone, though. Most other river systems along the Northeast coast reported poor shad runs, with the Connecticut and Merrimack rivers tallying their worst runs ever, leading biologists to speculate that coastal conditions may have affected the annual migration into freshwater rivers. They hope the fish that stayed away this year may come back to boost spawning runs in 2006. Past dips in spawning runs have often been followed by strong years. In Virginia, John Olney, a fisheries scientist at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science who monitors shad runs in the state’s main rivers, said “the York River had a very disappointing run. The run was late and probably lower in strength on the James and Rappahannock as well.”

The news was not much better on the Potomac, where Jim Cummins, a biologist with the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin, said his survey nets were catching only about 60 percent as many shad as the past two years. “I thought the run would be a bigger one this year,” he said. And on the Susquehanna River, only 68,926 shad were carried over the Conowingo Dam by the $10 million fishlift completed in 1991. That was far below last year’s 109,000, and a disappointment to biologists who had hoped that fish hatched during 2001, when a record 193,574 were carried over the dam, would begin returning to spawn this year. “We were expecting a big year because we figured we would see the 4-year-olds coming back from that,” said Richard St. Pierre, Susquehanna River Coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “But it didn’t happen.”

The exception was the Patuxent River in Maryland, where spawning populations were up—mainly because the population has only started to build after years of stocking in the river. “We saw a lot of American shad this year, probably more than ever,” said Brian Richardson, of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. “We probably should see those numbers based on our stocking progress. We started stocking real heavily in 2000.”

The exception was the Patuxent River in Maryland, where spawning populations were up—mainly because the population has only started to build after years of stocking in the river. “We saw a lot of American shad this year, probably more than ever,” said Brian Richardson, of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. “We probably should see those numbers based on our stocking progress. We started stocking real heavily in 2000.”Rebuilding American shad populations has been a cornerstone of the Bay restoration effort because they unite the watershed’s large tributaries with the Chesapeake and coastal ocean. Shad are an anadromous fish—they spend most of their lives in the ocean but return to spawn in their native freshwater rivers, perhaps swimming hundreds of miles upstream. Millions of shad once filled the region’s rivers each spring during their upstream migrations. Shad was the Bay’s most valuable commercial fish species in the early 1900s. But decades of overfishing, combined with pollution in spawning areas and the construction of dams and other river blockages have reduced shad runs to a fraction of their historic level. To help restore shad, fishing in the Bay region was phased out in the 1980s and 1990s, and more than 1,300 miles of waterways have been opened to migration through the construction of fish passages or dam removals. Also, millions of hatchery-reared juveniles are released each year with the hope that they will return four to six years in the future to spawn, thereby building a “wild” population in the rivers.

Despite this year’s weak spawning run, the biologists said they were on track to meet the Bay Program’s goal of stocking between 15 million and 25 million young shad a year, although the numbers will be well below the record of 36 million stocked in 2000. Although there were fewer fish to collect eggs from, biologists reported that egg survival was better than normal, allowing more larvae to be reared in hatcheries. Maryland had its best-ever hatchery production, Richardson said, with about 3.2 million young fish produced, of which nearly 2 million went into the Choptank River, 700,000 into the Patuxent and more than 500,000 into the Nanticoke and Marshy Hope Creek, one of its tributaries.

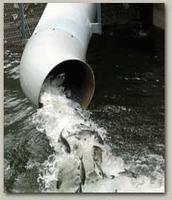

In Virginia, 6.4 million shad went into the James River and its tributaries, and 3.4 million went into the Rappahannock River above the recently removed Embrey Dam—the best stocking year so far for that river, according to Tom Gunter of the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. The Mattaponi and Pamunkey tribes also continued stocking efforts in the York River tributaries which bear their names, although figures were not available. Hatchery production was off sharply in the Susquehanna River, largely because of difficulties in getting enough egg-bearing fish from the Hudson River, St. Pierre said. Only 3.6 million shad were stocked in the Susquehanna—a river that has often received 10 million or more in past years. But the hatchery-reared fish may be boosted by natural spawning in the Susquehanna this year, where four major hydroelectric dams cross the first 55 miles of river. Utilities owning the dams have spent tens of millions of dollars building fishlifts and other passages in the past 15 years to help the fish get upstream.

Although the number of shad passed over the Conowingo Dam—the first dam encountered by the fish—was off sharply from last year, the number passing the next two dams, Holtwood and Safe Harbor, increased dramatically. Of the 68,926 shad lifted over Conowingo, 34,189 also passed Holtwood and 25,425 passed Safe Harbor. The Safe Harbor figure is important because suitable spawning habitat begins above their impoundment. “In terms of what it means for the program, this is a much better year than last year simply many fish got to spawning waters,” St. Pierre said. Last year, by contrast, only 2 percent of those fish counted at Conowingo reached spawning water above Safe Harbor. Twelve times as many shad made the journey in 2005.

St. Pierre said that this year’s widespread decline in shad abundance from the Mid-Atlantic through New England cannot be explained by excessive fishing pressure, dams or pollution. In fact, the Chesapeake has a longstanding moratorium and all ocean fisheries were closed this year. “Shad spend most of their lives at sea, beyond our protection or even monitoring capability,” said St. Pierre. He speculated that “even minor changes in marine currents, temperatures, food availability, predation or other factors could adversely affect wide-ranging stocks such as shad.” By Karl Blankenship Published in Chesapeake Bay Journal

No comments:

Post a Comment